With commentary by Paula Iturralde Pólit

There are situations in which we wish to innovate or transform the environment around us -whether physical or social- because changes are necessary and part of our own evolution as people.

The space to share with friends and family, the workplace, an area to relax or to be alone, and countless other situations in which we like certain conditions to be met in order to be satisfied and therefore influence our performance.

It is human nature to seek to live in environments that stimulate our lifestyle and customs; we are constantly building our ideal niche.

The term niche is widely used in ecology. It refers to the space used by species to carry out their activities and where they fulfil their fundamental roles as living organisms, from finding food and shelter to interacting with other species (such as predation and competition).

This space that determines the lifeform of each species is defined by climatic conditions and re-defined by the available resources that allow each individual to survive. That is why it is so intangible.

The renowned Chilean ecologist Humberto Maturana says that organisms constitute a unitary relationship of existence with their niche, which is delimited by the interaction of their behaviour with physical space. That space does not pre-exist but is constantly modified.

In human beings, something similar happens, after all, we are animals and part of a whole that we call nature. We also create our environment based on the characteristics of our surroundings. Inevitably we transform it while triggering a series of behaviours that define our relationship with the environment.

Thus, the design, comfort, habitability, and even the space we have to interact with others will have an impact because our ability to live together is inspired by the environment.

In this context, we present the architectural proposal that Esteban Matheus made for and with the Mushullakta community, consistent with the idea of "creating a niche,” which is part of an integrated space to learn to share.

Through Humans for Abundance, we are learning that to regenerate ecosystems; we first need to renovate and recognize the action and role of the humans who live and interact with these ecosystems.

Our best example is what we are learning by partnering with the Mushullakta community, located in the upper Amazon rainforest of Ecuador.

Mushullakta Domain

Mushullakta - as is the case in many local communities around the world - is caught in an identity struggle between its traditional way of seeing the natural and the human as undifferentiated, versus the more globalised worldview that sees nature as a commodity.

When we met them, the families of Mushullakta had deforested parts of their land to plant monocultures of Guayusa. They had cut down areas of their polyculture ”Chakras”, which are the contemporary versions of pre-contact domesticated forest lands mentioned in a previous post which you can read here.

After knowing this part of the story, we asked them how we could support them. They shared their desire to regenerate their land because they consider the forest part of their identity.

A New Environment

As they described their envisioned future, both for the community and the land, it became clear that forest restoration prevailed as part of a larger social and cultural regeneration project.

The project includes education programs for their children to acquire internet skills, trilingual education, and learning traditional medicine.

Their dream was to have a structure that would function as a tree nursery for reforestation, a guesthouse, and a sacred area for all the families. This includes areas where they could gather together for the morning ritual of Guayusa Upina (read more about these dream ceremonies here). In addition, they considered orchards and gardens that kids could use as playing areas. All in one place.

The community had a clear picture of what they needed from the very beginning.

Puma Wasi

Puma Wasi, meaning the House of the Puma, is the name the community chose for their vision. They wanted to restore the puma's habitat. They wanted their land to become diverse and abundant enough for the puma to return to the forest. The idea became pretty clear; by protecting the puma, they would indirectly protect other species that make up the ecological community.

With this in mind, we developed three initial phases to start making this vision a reality:

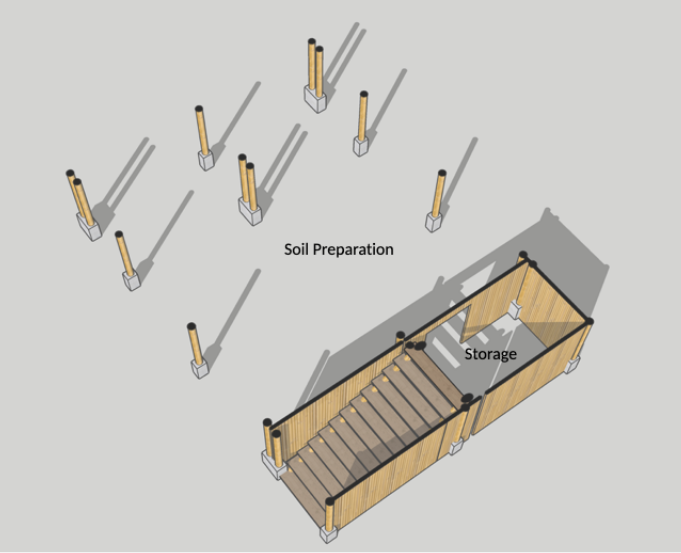

To build a greenhouse or nursery to start growing the seedlings of indigenous trees to initiate the process of reforestation.

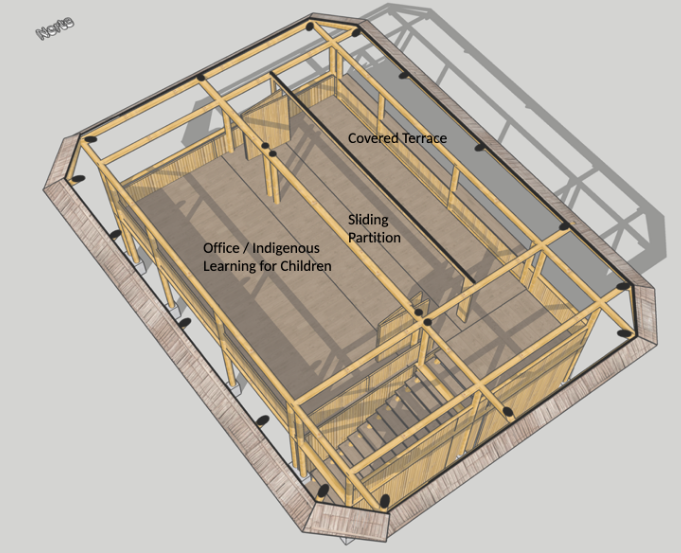

A multi-purpose structure that allows soil preparation for the seedlings and space above for teaching their children and office space.

Create a larger structure that can gather for their Guayusa Upina rituals. It can house more guests and volunteers to share their knowledge of forest regeneration.

Phase 1: The Nursery

We can happily say that the nursery is done! We obtained a grant with Terraformation that included a “greenhouse kit”.

In addition to the nursery the community included a rainwater collection system. The rain water collected will be transported through canals to a fish pond where the community will raise fish. The fish waste will serve as organic fertilizer for the plants and the fish themselves will contribute nutritional value and a balanced diet for the community.

The community is already using the nursery to organise their seeds and grow seedlings which they will use to restore but also to share with other communities

Phase 2: A Renewable Building

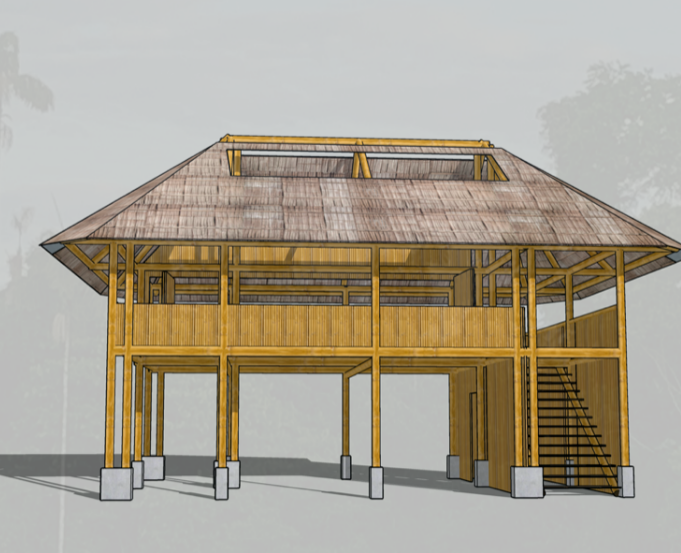

We explore utilising bio-materials that can also enhance local and renewable economies. A traditional building material that is used in the region is Caña Guadua, the indigenous form of bamboo. A very resistant material that has been compared with steel.

Moreover, it can absorb energy and support the structure when seismic activity occurs (which is not uncommon). The best part is that Caña Guadua grows (quickly) in their land, and they all they have to do is treat it with natural preservatives to dry it out before using it.

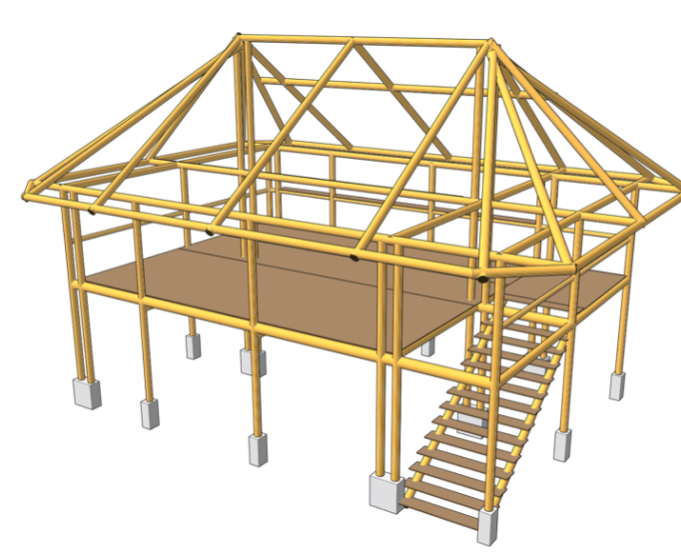

Based on the community’s knowledge of how to employ Caña Guadua, we developed a simple structure that incorporated traditional strategies of building shelters in the rain forest, including:

A steep roof that protects and sheds the constant heavy rains.

Raising the structure to protect from ground moisture and other animals/insects.

Having a covered but outdoor space for activities during storms and extreme heat.

The bottom level is covered area which is open on all sides for soil preparation and mixing as well as a storage area under the stairs.

On the upper floor the families themselves can teach their children about indigenous knowledge and topics. Additionally, it will function as an office when needed. This enclosed area has a sliding partition that connects and expands into a covered terrace area, becoming one ample space that still allows the eastern winds to ventilate and cool the building while protecting from the rain.

We are exploring the use of Pambil leaves and other vegetable fibers from local palm trees, traditionally used for roofing material in the area. The roof will also incorporate a skylight facing away from the predominant wind and storms

With a complete design, the community started building the structure themselves, with most materials being locally sourced. The foundation and the main structure was ready, and the complementary side columns were added for strength and lateral support.

Phase 3: A place to gather

We are looking for ways to shape their vision so that this can manifest who they are as a community while also being functional when dealing with the standard climatic conditions of the place. Frequent storms, heat, and high humidity conditions increase the speed at which organic building materials deteriorate. Hence, the structure may need more frequent maintenance.

After being invited to take part in their morning Guayusa Upina ritual, where the dreams they have are shared and shape their days, we realised that the central space for a new structure should be a place that allows for this ritual to happen.

Also, they have an excess of Guayusa trees that need to be cleared to make space for the regeneration of their traditional polyculture agroforestry. They want to experiment with Guayusa wood as a building material. This may give a new meaning to a painful episode in the community’s recent past.

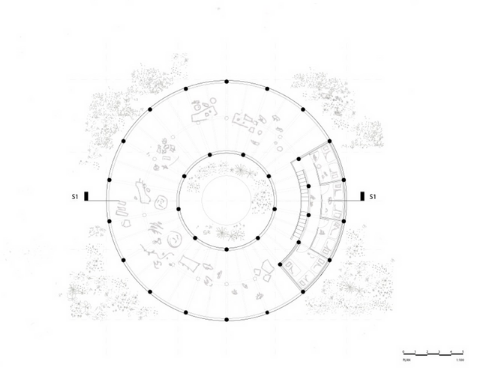

The simple concept is to take the sectional relationship of a traditional house but extrude it in a circle. This creates an internal central space for the Guayusada while also keeping a completely open and egalitarian face in all directions outward.

The pitched roof creates space for a second-floor mezzanine, where bedrooms for visitors, volunteers, and guests can be accommodated.

Creating a Unique Niche

In summary, what we are learning from these incredible collaborations with indigenous communities in the rainforest is that DESIGN AND URBANISM CAN BE SYMBIOTIC WITH THE AMAZON.

The notion of a pristine Amazon is not necessarily absolute, as ancestral communities have inhabited it for hundreds of years, but its relentless destruction is palpable. It is vital to create a new strategy so that we may save not only the Amazon but our own human existence.

WE BELIEVE THAT RURAL DESIGN CAN BECOME AN INTEGRAL PART OF A SOCIAL, ECONOMIC, CULTURAL, ECOLOGICAL, AND SPIRITUAL REGENERATIVE PROCESS in the Amazon and other critical ecosystems around the world.

According to Humberto Maturana, our biological way of living integrates our culture in the same way as talking and reflecting take part in the niche we inhabit. This niche can trigger structural changes in living beings and the other way around. In other words, just as we can define our environment, the environment also defines us because we are talking about two entities that cannot function independently. Without one, the other does not exist.

We, as human beings, constitute our environment. This is how the concept of autopoiesis is created; it means “making oneself” because everything surrounding us influences our emotions, creativity, and connections with other people. Ultimately it affects our way of living.

This is precisely what the community of Mushullakta has achieved with Esteban’s help. Although an expert elaborated the new structure design, the inhabitants of the community were the ones who discussed as a group to agree on one common idea for the scenario where they could reflect on their projects and dreams. The ideas were adapted by Esteban, who provided them with an environment in line with their way of relating to nature and in which they could develop their restoration projects.

Our environment influences what we do, and it is essential to design it so that we know it is the right one to achieve our goals.